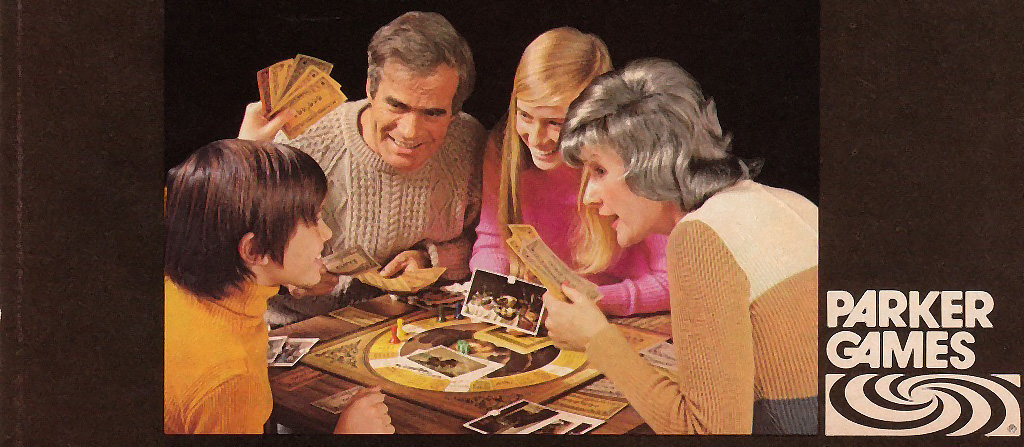

My last essay was a critique of nostalgia, and so to mix things up this post will be a discussion of something from my youth for which I have a great deal of affection, and that is Parker Brothers graphic design from the 1970s. This is admittedly a niche interest, even for me, but I hope you’ll be indulgent. Perhaps you, too, will come to love these beautiful and strange designs.

From around 1970 to 1980, the Salem, Massachusetts-based Parker Brothers (now a brand of Hasbro) published games whose innovative and fanciful designs drew inspiration from Pop Art, Op Art, and Madison Avenue advertising. They had boxes, boards, and components that reflected the most current techniques of printing and plastics molding. They were witty, silly, and weird. The other main players in American games at the time were Milton-Bradley, whose art tended towards cartoony, corny, and flat designs, and Ideal, whose games (like Mousetrap) were mostly showcases for their novel plastic components.

Parker Brothers design stood out for its style and sophistication, and even as a young nerd I could see that it was special. In fact, I believe they were my introduction, at the age of seven, to the whole concept of graphic design. This isn’t to say that the games were good in the sense of being fun or engaging to play; a lot of them were re-skinned versions of the basic race-around-the-board type that had been popular since the Uncle Wiggly Game. But they looked amazing and they were different.

There’s not a lot of sources of information about the company, but there is one very interesting book, The Game Makers : the Story of Parker Brothers from Tiddledy Winks to Trivial Pursuit, which was written by Philip Orbanes in 2004 and published by Harvard Business School Press. From this book I learned that starting with its founding in 1883, Parker Brothers was a family owned operation, and its ethos was decidedly conservative. It produced child-friendly tabletop games that it purchased from independent creators, with little to no research and development and with a small factory that printed simple boards and boxes and made components from simple materials.

Along the way they picked up some major properties, like Monopoly and Cluedo, which was rebranded in America as Clue, but they didn’t develop these in-house and they didn’t really have a marketing strategy of any kind. But all that changed in 1968 when the company was sold to General Mills—yes, that General Mills, of Cheerios fame. After the departure of one president who wanted to cash out and retire, and the death of another who died of lung cancer, executive vice president Ranny Barton took the helm, and he immediately replaced the head of manufacturing and the head of sales. Orbanes writes:

In one fell swoop, Ranny Barton had changed Parker Brothers from a family-run, conservative operation to one now seeking high-flying M.B.A;s and marketing wizards in a quest to again double sales. Ranny […] would oversee a group of executives who were experts (165-166).

For the first time, the company had project leaders and marketing staff (largely on loan from General Mills). They brought in professionals in design, production, and printing. They bought a new state-of-the art press capable of much finer detail and vibrant colors, and they switched to making their components out of injection molded plastic. They were out to compete, and that meant to advertise on the new medium of television, and to be distinctive.

Okay, that’s more than enough backstory. Let’s look at some of the games from this time.

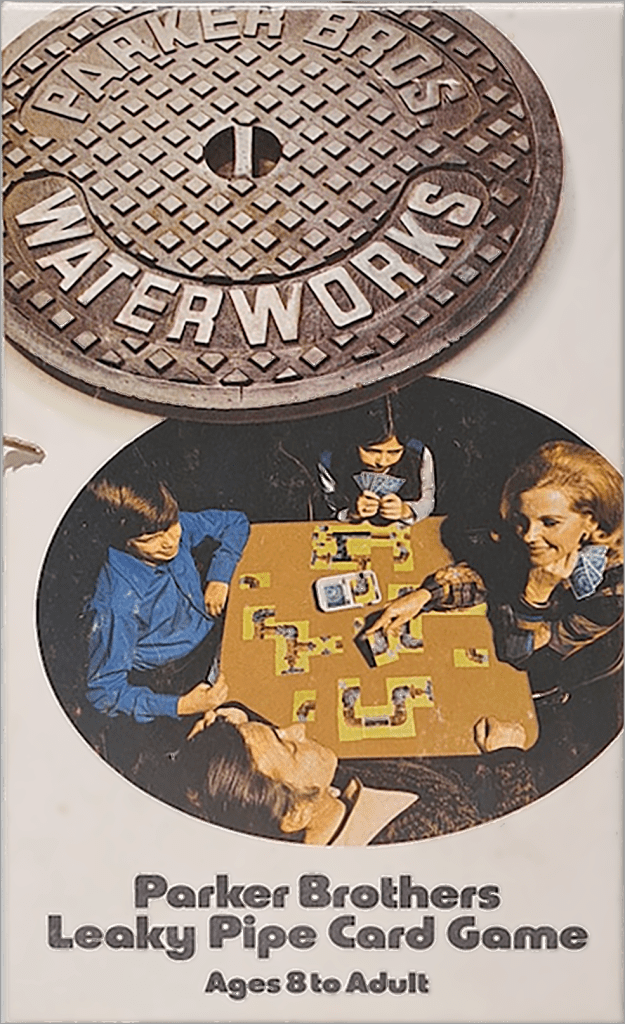

Waterworks (1972)

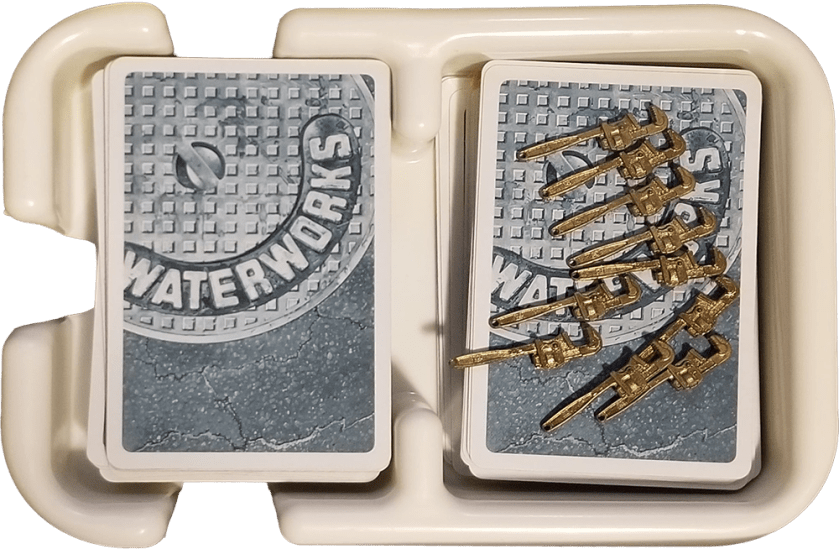

I remember coming across a used copy of this game at a school tag sale when I was in first grade. It looked like nothing else I’d ever seen. The cover art was sparse and focused on its photography. The text was set in Blippo, which seemed shockingly futuristic (it was actually designed in 1969). Most of all, the diegetic title on the manhole cover felt absolutely tangible. I splurged on the 30-cent purchase (my allowance at the time was a quarter).

Inside, the cards were wonderful, featuring detailed, photorealistic depictions of pipe fittings, handles, and spouts. They came in a draw/discard bathtub. And there were tiny brass monkey wrenches (perhaps using the existing Clue wrench molds). Everything was designed to be tactile and engaging.

Waterworks was designed by Mattiene Moustakas, although whether she designed the gameplay and components, or illustrated the cards, or both, is unclear. She certainly has a crazy resume. As for the play, a modern gamer will recognize it as a tile placing game such as Carcassonne; one chained one’s cards together to make a line from handle to spout, while playing pipe junctions and leaks on the opponent’s spread. It was…ok. It was certainly different from the card games I’d played, which were basically War and Solitaire1.

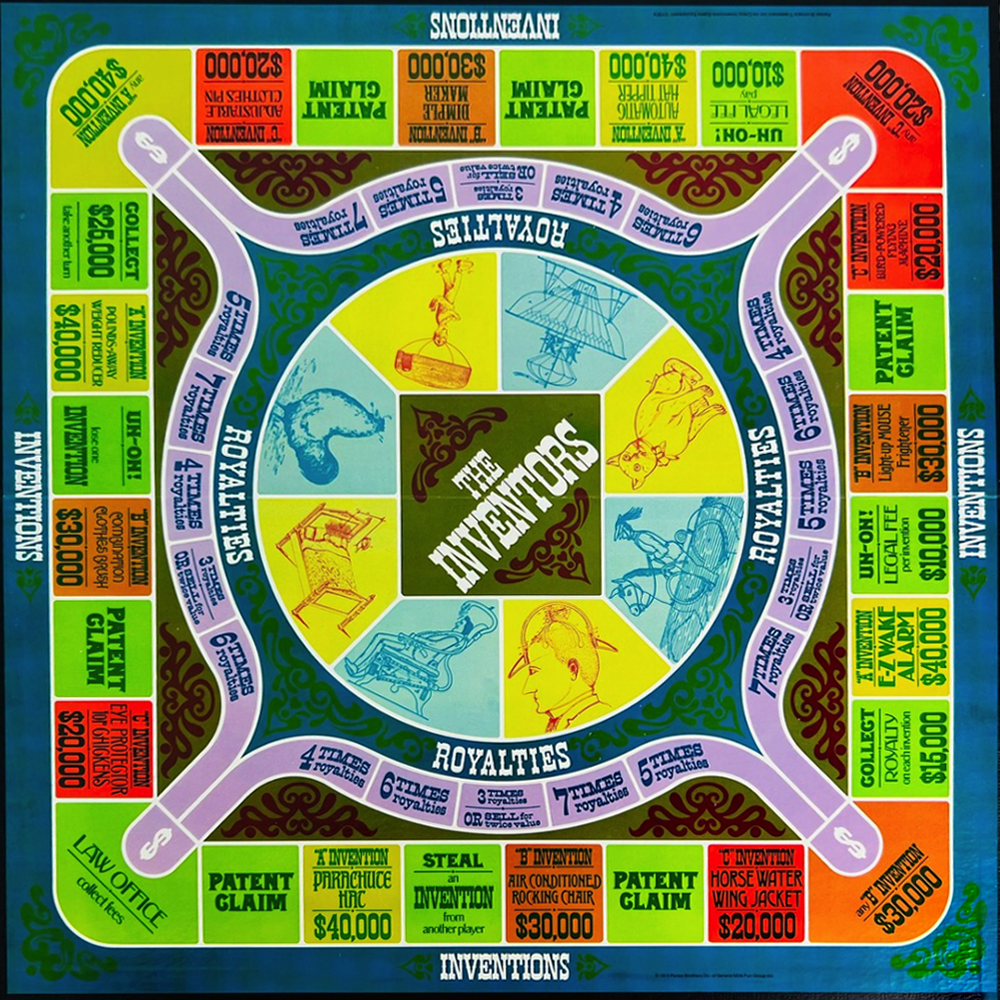

The Inventors (1974)

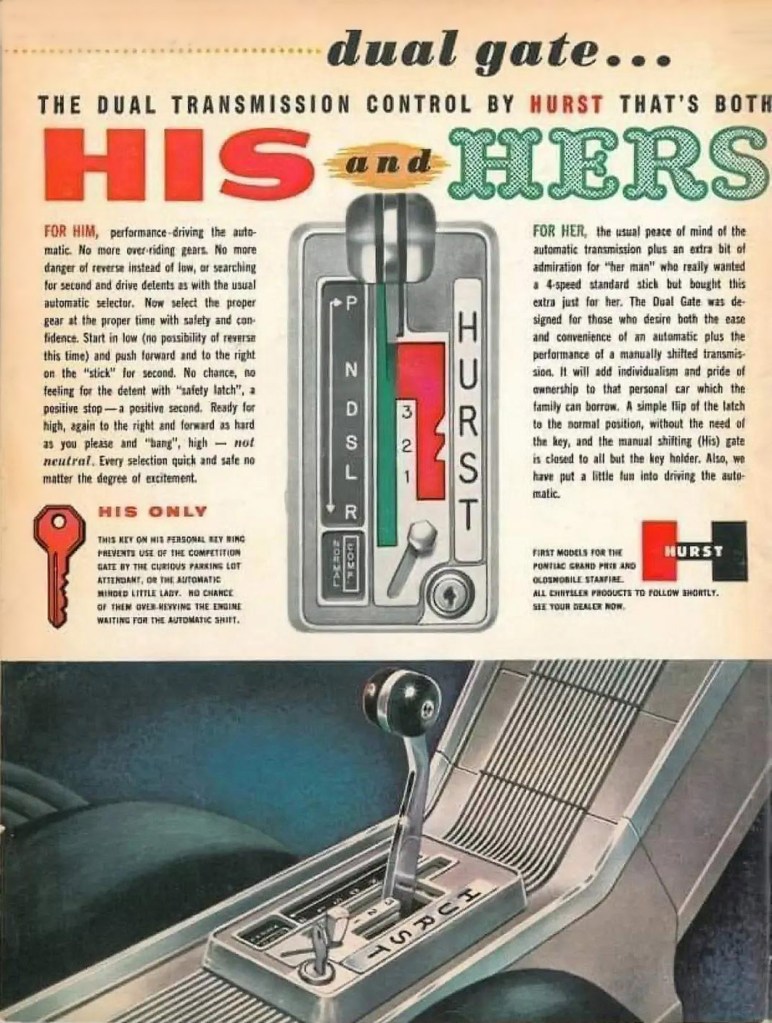

I’ve mentioned before that the 1970s had a strange retro fad for “old-timey” things, by which I mean Americana from about 1890 to 1905. I am at a loss to explain this. It was a time of serious social problems, from race relations to stagflation. Perhaps there was a longing for a mythical past. The counterculture had drawn heavily on Art Nouveau in poster design, and maybe this trend was breaking into the wider culture. In any case, The Inventors was themed around patenting odd Victorian-looking inventions. The cover art was a highly staged studio shot with models in costumes with props. It featured many of the gadgets referenced in the game, as well as an inventor holding the game itself on his lap, and that kind of self-referentiality was catnip for me. (By the way, the text on the bottom right is in a typeface called Desdemona, which originated in Vienna and has always sounds drama club to me.)

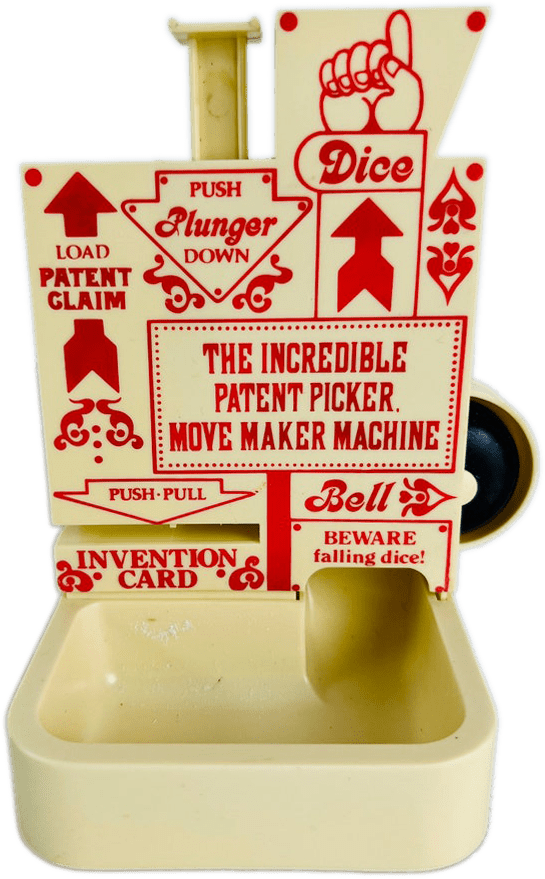

The board features a pastiche of Victorian typography and day-glo colors. It features two different tracks to circle the board, but the filigrees and other ornamentation make it seem much more complex. There are handsome cards that feature descriptions of the various inventions to be patented. But the real star of the show is the centerpiece, “the incredible patent picker, move maker machine.”

This chunky bad boy held the metal clip-on numbers that were the game’s patents, and the “push-pull” dispenser never really worked because the invention cards would bend and fray when you stuck them in. But that didn’t matter, because the real attraction was the dice chute. You placed the dice into the hopper and hit a plunger and they would roll into the tub below, all while ringing a bell.

The Inventors was designed by Jeffrey Breslow, who was a student of Marvin Glass, a powerhouse designer that has created many of the most recognizable toys of the 20th century. Breslow, working with Glass, also designed Ants in the Pants. As for The Inventors’ gameplay: meh. It vaguely resembles Monopoly in that players attempt to succeed financially by developing their properties. But for the most part it’s circling the board in parallel to one’s opponents, with perishingly few actions that directly affect the other players.

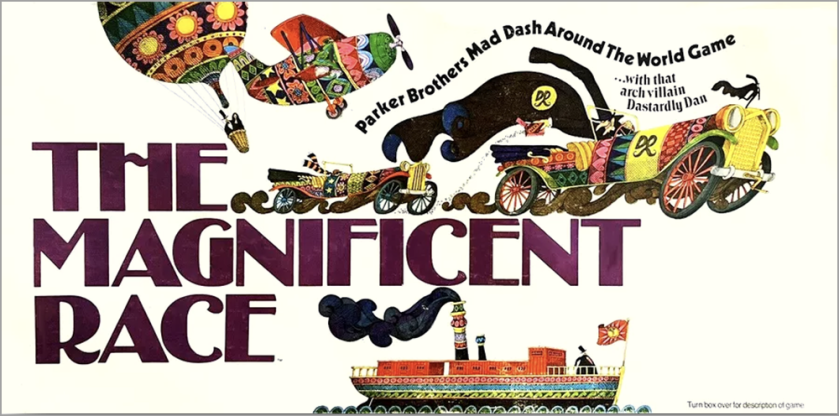

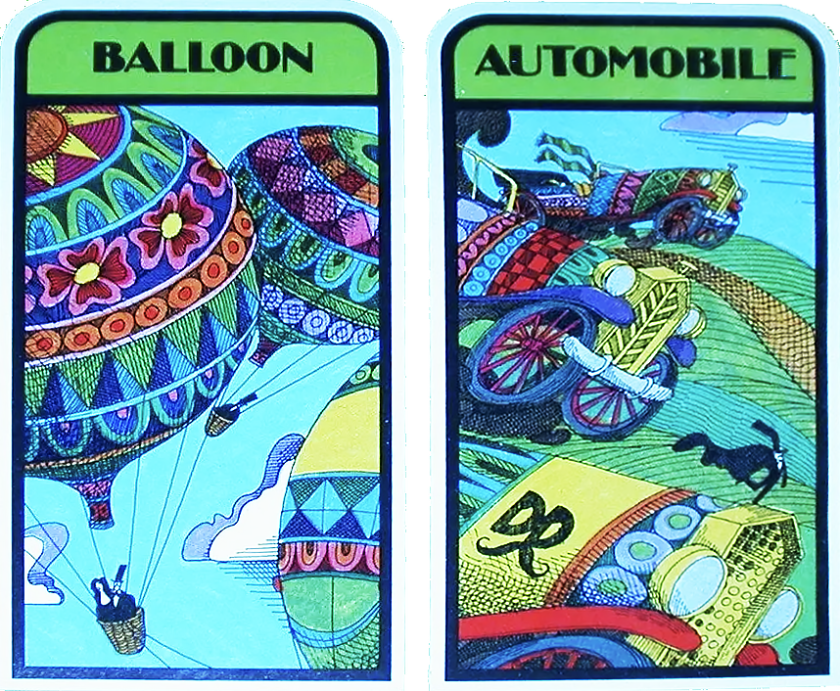

The Magnificent Race (1975)

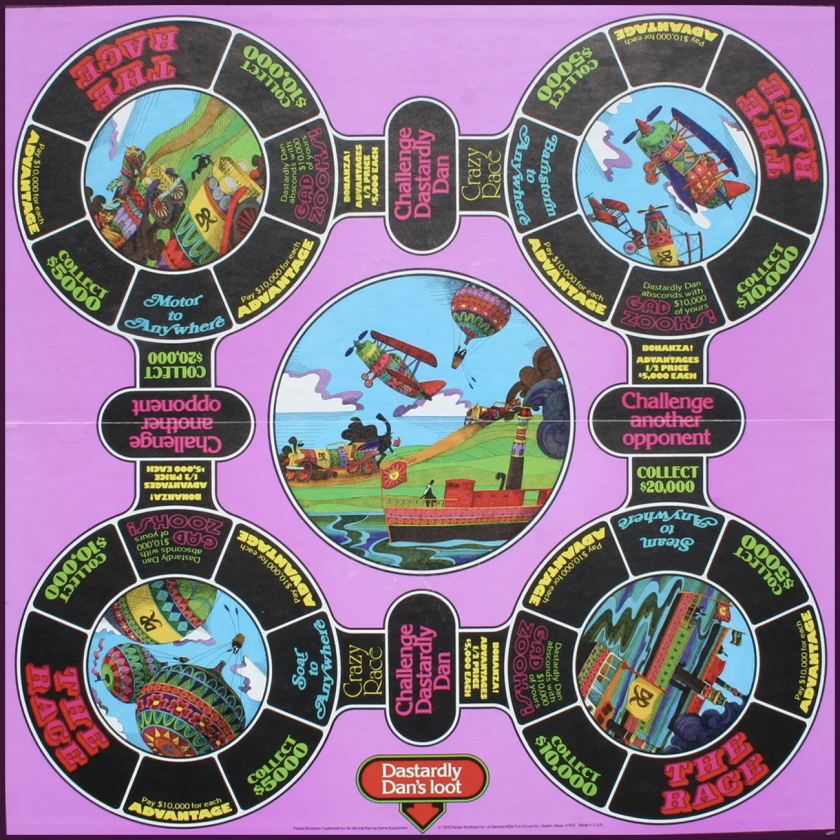

Another old-timey game, The Magnificent Race obviously takes inspiration from Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days. The players must circumnavigate the globe using cars, ships, planes, and balloons. The gimmick of the game is a non-player-character (before there even were NPCs) called Dastardly Dan, represented by a purple marble, who can interfere in, and even win, the titular race.

The game’s board shares its typography, color palette, and even curvilinear forms with the Inventors’ board, and I’m pretty sure the same designer did both. One innovation to this board is the paths are not directional, and players may move there arrows in any direction. This may not seem like a particularly distinctive feature today, but it was unusual in 1975.

The components here pull out all the stops. There are big chunky arrows used as player markers, layout cards on which to place “advantages,” a pegboard to track overall progress around the world, and a spinner with colored marbles (including Dastardly Dan) that determines the winner of each of the series of small races that make up the game. Each player drops in a number of marbles based upon their advantages, the device is spun, and the first to drop into a divot near the center wins.

When everything is set up it’s pretty impressive. Fun fact: the groovy fake money for the game is printed on green and purple paper that isn’t shelf-stable. I know this because the bills in the copy I purchased for my kids many decades later crumble apart at the slightest touch.

The game was designed by Bill Cooke, who co-designed Boggle (also originally published by Parker Brothers). On his Facebook page Cooke has photos including the original schematic drawings for the spinner. But for me the real attraction is the scratchy, cartoony pen drawings, which recall some of the more elaborate designs of Milton Glaser. I would dearly love to know who the illustrator was for these.

As for the gameplay…this one’s a real let-down. All of the bells and whistles can’t hide that at its core it’s a random chase around the board. However, the spinner is a lot of fun, especially when the Dastardly Dan marble wins.

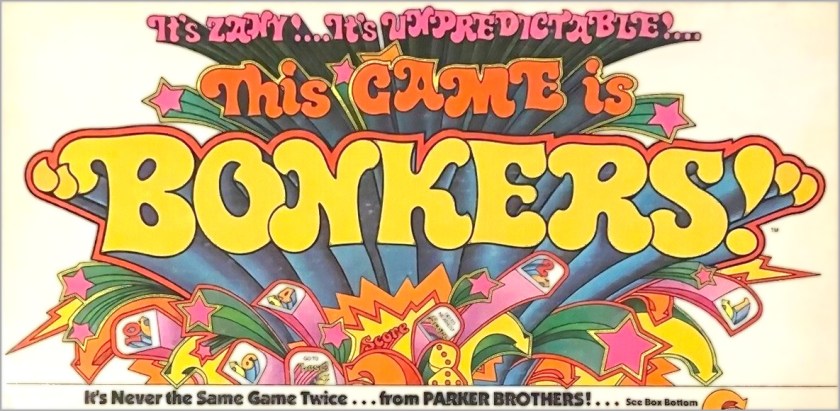

Bonkers (1978)

Or to refer to it by its full name as printed on the box, This Game is Bonkers. This was not a game my family owned but I played it at friends’ houses and it had an earworm-y television commercial that probably most Americans in their 50s can still sing today.

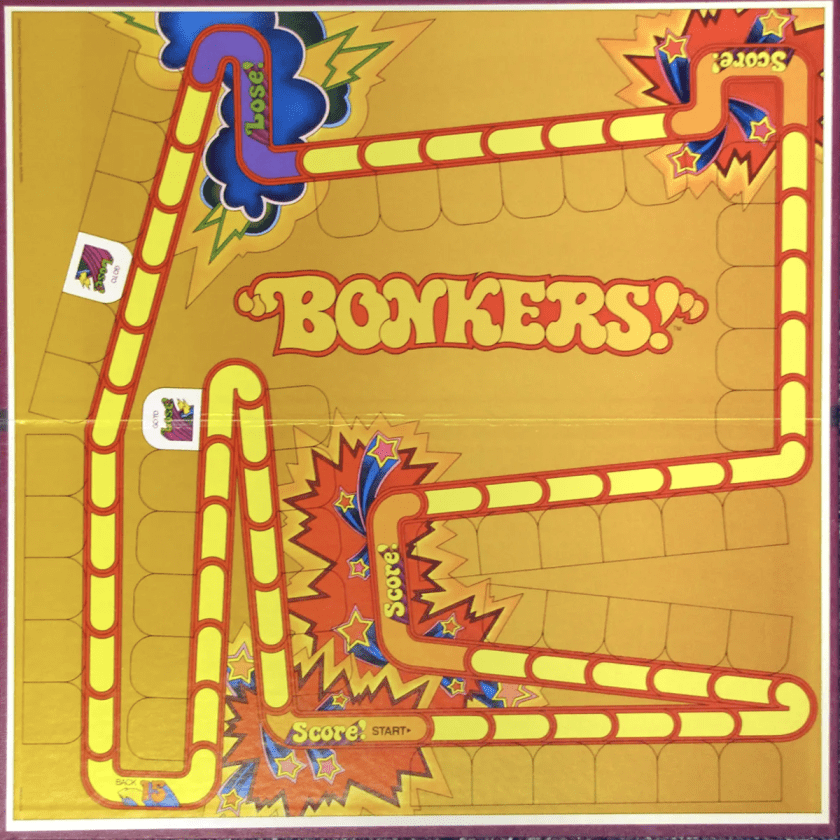

In the Bonkers graphic design Parker Brothers reached an apotheosis. For years they had been cribbing from the cheekier parts of Madison Avenue; here they went full-on Peter Max with shooting stars, lightning bolts, volumetric arrows, and exclamation points everywhere. The board starts pretty empty, but players fill in the spaces with U-shaped cards that change the flow of movement, directing tokens forwards and backwards and eventually into spaces that score or remove points.

The design couldn’t be more frenetic or bold. Unfortunately, the graphics promise a zanier time than the gameplay delivers. The mechanic of players altering the rules of the game as they go is a good one (see modern games like Fluxx), but that’s not really what’s happening here; instead, the normal clockwise race around the board is being lengthened by digressions. It’s still a fixed track. But man, does it look great.

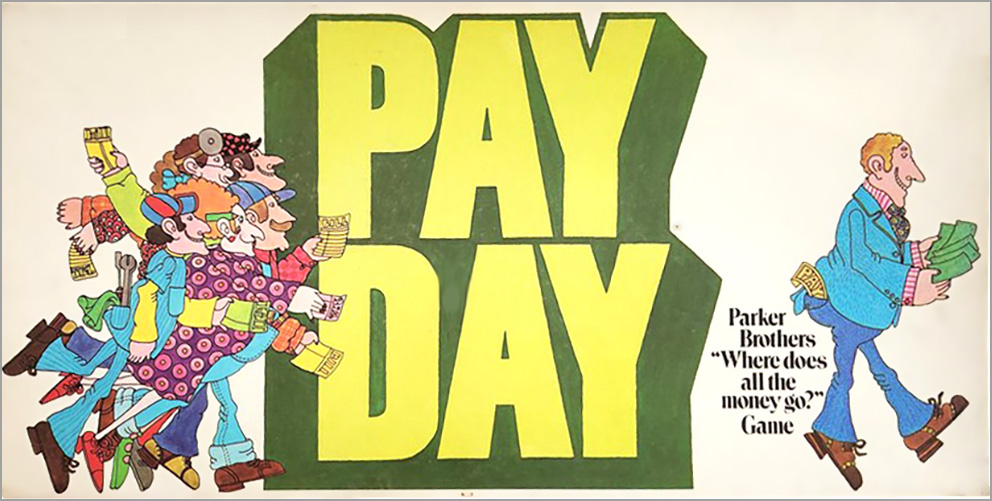

Bonkers was designed by local boy Paul J. Gruen, who lived in West Newbury, just a half-hour drive from Parker Brothers. He also designed Pay Day (1972) for Parker Brothers, another game whose original graphics had pop art origins—in this case with illustrations resembling those of Heinz Edelmann, character designer for the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine (1968).

That’s enough

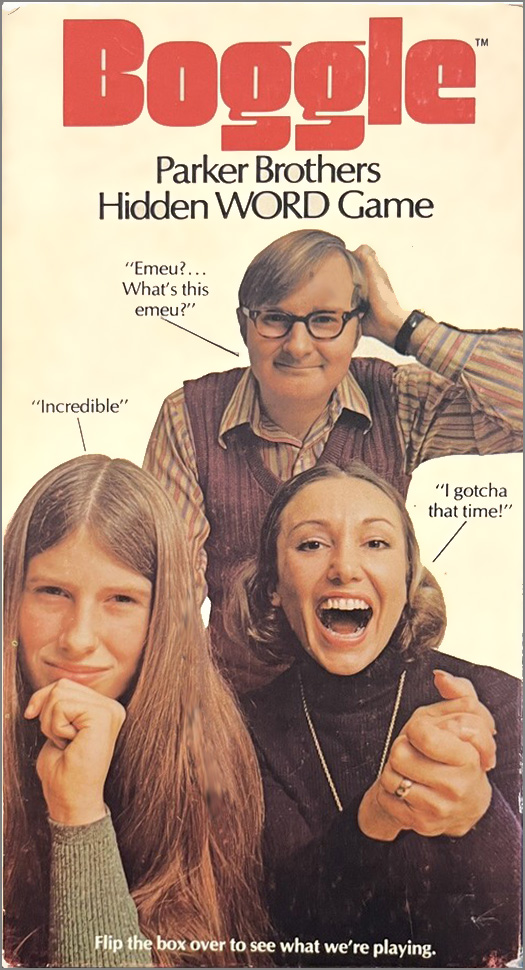

I could go on for hours, and it probably feels like I have already. There’s so many wonderful designs from this period: Vertigo (1970), Masterpiece (1970), 10-Four Good Buddy (1976), The Mad Magazine Game (1979). Even the original Boggle (1973) cover art is a crazy snapshot of a time of weird innovation: it didn’t actually feature the game2.

As the 70s ended, Parker Brothers swung heavily into electronics with toys like Merlin (1978) and their own line of cartridges for the Atari 2600. And in 1985, General Mills merged the company with Kenner, then sold it to Tonka in 1987, before everything eventually got bought up by Hasbro in 1991. But for a brief time in the 70s, Parker Brothers was the one game company that was distinctive, brassy, different. The games themselves were hit-or-miss, but the design always landed.

- As an aside, I learned the version of Solitaire I knew from my mom, which was a hard-as-nails version that I have never seen anyone else play, so I don’t even know what it would be called. Years later I would learn that most kids played Klondike, which I would scoff at as a baby game. ↩︎

- Also it was set in Optima! ↩︎