Plot: We open to the melodious but stern voice of Miss Greer Garson whose schoolmarmish reading of scripture lets us know it’s time to sit up straight, as there will be a quiz following. It’s the time of Caesar Augustus and there’s a “cruel tax”—although what does she think, those roads just grow on trees?—that requires everyone to shuffle through the desert in bleak, single-file lines. Everyone, that is, except the n’er-do-well entertainer, Ben Haramed (Jose Ferrer), and his cross-eyed companion, Ali (Paul Frees), who seem to be strolling through the sand dunes without a destination or provisions. Perhaps the story that follows is merely a hallucination brought about by extreme dehydration.

Here comes the titular drummer boy, Aaron (Teddy Eccles)—who is drumming, because what else would he be doing? He’s accompanied by his “old friends:” the donkey, Samson; the lamb, Ben Baabaa, and the camel, Joshua, all of whom are swaying about on their spindly hind legs as though they’ve stepped out of a particularly apocalyptic Bosch painting. The catty Aaron is unimpressed with the animals’ footwork and spurs them on like a stage mother: “be lighter! Happier!” Ali notes that “it is said” that Aaron hates all people—at eight years of age, Aaron already has a rich body of folklore surrounding him.

Ben Haramed and Ali take Aaron and his friends captive as the title song plays, unhelpfully. Ben Haramed reveals his nefarious intent of putting on a variety show for the taxpayers through the song “When the Goose is Hanging High.” The connection between poultry and show business is left unmade as Garson leads us a flashback explaining why Ali hates people: this involves the onscreen knifing of his father and the offscreen murder of his mother, as well as the destruction by fire of Aaron’s home. Happy Holidays, everyone!

The horror continues within the bleak gray walls of Jerusalem where Aaron is compelled to perform for a leering crowd while wearing a painted smile that would make Heath Ledger cringe. “Why can’t the Animals Smile?” he sings, as his furry companions stage a bacchanal in which they pretend to be other creatures, and we recall the words of Lovecraft, that the most merciful thing in the world really is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. All this proves too much for Aaron, who finally snaps and turns on the crowd before a passing of the keffiyeh can garner a single shekel.

As luck would have it, outside the city the troupe runs into a trio of wise kings (all Paul Frees), who are uninterested in percussive music but are happy to purchase Joshua, having killed their own camel by loading it with an industrial pallet of Frankincense and Myrrh from Sam’s Club. Aaron is none to happy about this and runs after the kings’ caravan to be reunited with Joshua. There hasn’t been quite enough tragedy in this children’s story, so Baabaa is abruptly run over by an irate Centurion in a chariot, late on his way to a filming of Ben Hur. Aaron takes his dying lamb to the stable where the kings are, and finally notices this huge star in the sky thing that’s been looming overhead the entire time. Fortunately, the Messiah is hip to Aaron’s crazy beats and Baabaa is miraculously healed.

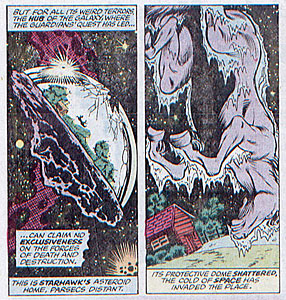

Notes: This show is based on the listless, monotonous,and inexplicably popular Christmas song, written by Davis, Onorati and Simonein 1958. It never ceases to amaze me that it took three people to write the thing. The gritty sets and misshapen china-doll character designs are straight from your nightmares—or perhaps a Cold War era animation studio somewhere in Czechoslovakia. Reflecting the emerging crafts movement that would dominate the early ’70s, everything is gritty and dirty and the palette runs the gamut of browns from dirt to mud. While the actual hills surrounding Jerusalem are quite lush with vegetation, this story takes place in what looks like the Gobi Desert, because it’s the Middle East, am I right?

For a children’s special, The Little Drummer Boy is pretty brutal: violent death, enslavement, and the Vienna Boys’ Choir all feature prominently. But it’s also earnest and honest in a way that, say, The Christmas Shoes isn’t, like a big sloppy dog that just wants you to love it and to forgive it for what it did to your socks. The basic message, that we should give what we can as we are able, is both theologically and ethically sound. But did they really have to make the bad guys Arabs?