The title of this blog, “Pathetic Fallacy,” is not just a great name for a punk band. It’s a literary and art criticism term for the cliché of attributing human emotions to inanimate objects or natural phenomena, like saying “the angry waves” or having a thunderstorm burst out just as your gothic heroine escapes the mansion and runs into the moors. If it isn’t obvious, the term is mean pejoratively.

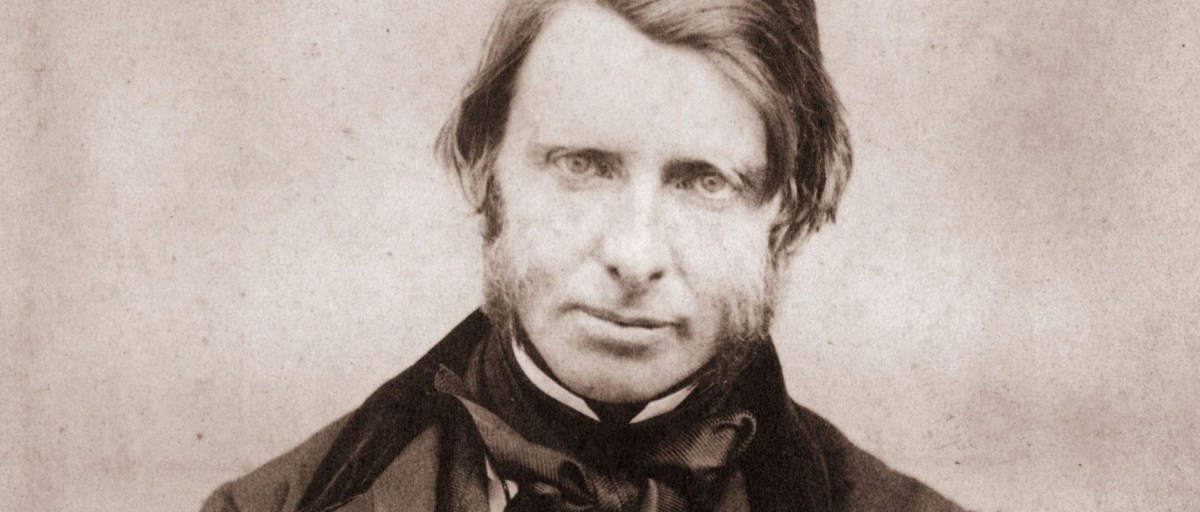

“Pathetic Fallacy” was coined by the Victorian critic and theorist John Ruskin (in the photo) in the third volume of his book series Modern Painters in 1856. Ruskin was taking to task the Romantic poets of the previous century, guys like Wordsworth, who might have written about clouds and daffodils but only as props to explore his own feelies. In the 19th century, “pathetic” meant “causing emotions” and “fallacy” didn’t mean “an error in reasoning,” but more broadly, “falsehood.” So the phrase could be restated as “emotional falseness.” Which is not a good name for a punk band and only a so-so name for a 2000’s indie one.

Ruskin was an interesting guy, an art historian who was a painter himself, a theorist whose work paved the way for environmentalism and for the arts and crafts movement, a champion of J. M. W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites. He was a social reformer and a philanthropist. At the height of his powers, Ruskin defined what art was and what it did, at least as far as the Victorians were concerned.

He was also a consumptive, depressed man who was abusive to his wife, attracted to adolescent girls, obsessed with Spiritualism (as in seances and that sort of thing), and whose ideas were largely swept aside by the Aesthetic movement in the 1870s and 80s. Today he is most famous for dissing the work of James Whistler, to the point of a retaliatory libel suit.

Critics are often, quite rightly, accused of gatekeeping. In 1939 the critic Clement Greenberg wrote the essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” stating that some art is good because it’s challenging and some art is bad because it’s popular1. In the years that followed, Greenberg worked with the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom to display artists like Jackson Pollock in communist countries, presenting them as paragons of American Individualism2. “Kitsch” as a concept was ubiquitous in the art world for decades—until another critic, Susan Sontag, struck back with her essay “Notes on ‘Camp.’“

Closer to our own time, Roger Ebert spent much of the last year of his life picking a fight with nerds online by insisting that video games would never be art. I dunno, if I were dealing with the terminal health problems Ebert had, I would not spend my numbered days annoying a bunch of surly Zelda fans. Also I find the project of defining “art” to be profoundly tiresome. Still, I will always love Ebert for the joy he brought to his work, the sheer enthusiasm he had when he was recommending a new movie that brought him delight. Like Garfield: the Movie.

I am fascinated and ambivalent about the critical process. At its best, criticism can provide context and perspective that makes the artistic experience richer and more social. It’s a game that we play that doesn’t tell us what a work means but gives us something interesting to think about while we choose what the work means to us. At its worst, criticism tells us to distrust our own tastes.

All of which is to say, I still think Pathetic Fallacy would be a great punk band.