Now that I have a new computer I have about three or four months to enjoy being technologically current before sliding inexorably back into obsolescence. For me (to my wife’s sadness) this means playing all the games my old computer couldn’t handle; this is approximately all of them.

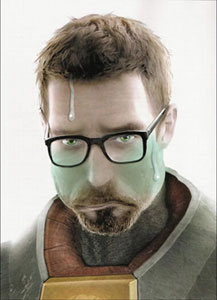

One evening about a week ago I was playing Half-Life 2 when I noticed I was feeling feverish and sweating; however, it’s summer in Boston and my basement can get kind of stuffy, so I turned on a fan and went back to whacking headcrabs with a crowbar. All at once I felt like throwing up, which I almost never do. I thought I had come down with something and I staggered to bed.

Feeling better the next day, I resumed the game and promptly needed a lie down, fast. So it had really happened: I’d become motion sick from a video game. The nausea wasn’t half as bad as feeling like a wuss; I had really become an old guy for whom freaking Half-Life was too heavy a dish. I waited for the floor to stop spinning and then picked myself off it. Then I typed “Motion sickness Half Life 2” into the search bar.

Turns out, this is a common problem with Half-Life 2, with discussions on dozens of message boards. Amongst all the jibes of n00b and fucking pussy go back to Tetris I learned that the likely cause of my reaction was the field of vision the game depicts. While most first-person games use a 90 degree angle of view (which roughly corresponds to real life), Half-Life 2 is set to 75 degrees, a sort of tunnel effect, like looking through a pair of binoculars (which can also make me a little dizzy). Fortunately, the game allows you to adjust the field of vision and I did. And that was it. The relief was immediate and complete, and I was able to continue through the game’s roughest, shakiest camera bits with no ill effects at all.

But while I’ve enjoyed the game and also like not being sick, the whole experience has been unsettling. My mind had been tricked by a tiny wedge of virtual sight into debilitating illness. Not only that, but the solution was mundane, mechanical, predictable. At some level I know that what I call myself is a series of biological and psychological processes, but the full implications of that are not something I dwell on. I don’t believe in an animating soul that is the truest self, but I do like to think that the mind is more than a chemical/electrical call and response. But those 15 degrees seem to say otherwise.