I was feeling a bit down the other day, what with (gestures at everything), and I said to myself, what I really need to do is some old-fashioned blogging, the kind from 1999, when the Internet was a wild an wooly place and SEO meant typing your search terms a few hundred times into your website’s <header>.

I still had an old Blogger site, but I wanted to move to something more contemporary. So here am I at my new WordPress home! Maybe having to pay for hosting this will spur me to write more often; anything’s possible. I have imported the old blog’s content but some of it glitched out, and some of it embarrasses me, so I am pruning a lot of the old content, and will continue to. Sorry if you are a completionist? I guess your best bet is the Internet Archive.

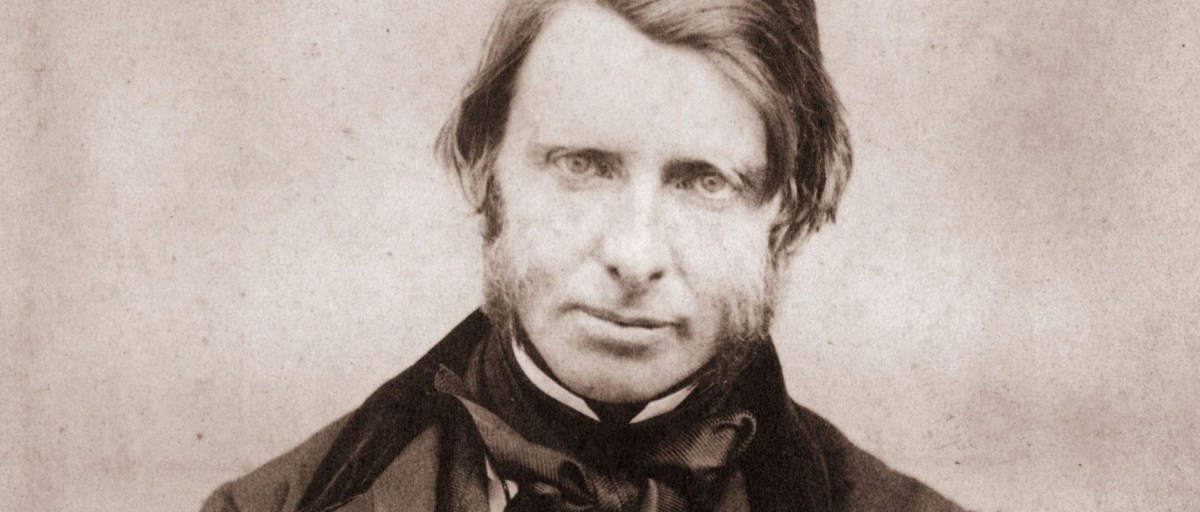

Anyway, to reintroduce myself: I’m John McCoy. I am married (for 35 years!) to a beautiful philosophy professor who is smarter than me and dad to two kids who are a biochemist and a medical student and will therefore be richer than me. On the Internet I’m best known for being older brother to my more famous sibling, Dan, of the comedy Flop House podcast. But I am second best known for my own, only occasionally funny podcast, Sophomore Lit. The tagline for this podcast is “where we re-read your 10th grade reading list,” and in the beginning my goal was to focus on stuff you only read in high school, like Catcher in the Rye or To Kill a Mockingbird. Also I wanted it to be silly. But as time went by two things happened: first, I ran through the obvious list of books, and second, I found that my guest hosts and listeners were genuinely interested in having a podcast that discussed formative literature sincerely. So these days episodes might be about kids’ books, like The Twenty-0ne Balloons, or things you might have read in college, like the Bell Jar. Anyway I’ve been doing this podcast since my mid-forties and now…I’m not in my mid-forties.

Speaking of kids’ books, Phil Gonzales of the Deep in Bear Country podcast and I did a podcast called Klickitcast, where we read through the entirety of Beverly Cleary’s books. It took a few years but we made it all the way from Henry Huggins (1950) to Ramona’s World (1999) in 33 episodes. This podcast was always going to end, but it has a special place in my heart and I miss it.

What else? I was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder in early 2020, just before the pandemic. Getting a late-life diagnosis was weird enough, but then there followed a sudden explosion of ASD discourse online as folks who became introspective during lock-down got diagnosed, or self-diagnosed, so I guess I was a trend-setter? A lot of people my age would have been clocked as autistic if we knew then what we know now. But self-knowledge is both liberating and anxiety-producing, and I’m still figuring this all out, as I probably will until I die (what we ASDers call “the Great Shutdown”).

Off the Internet, in the real world, I am an Assistant Director at an art museum. This probably isn’t as glamorous as it sounds to you, especially if you are a fan of The Da Vinci Code. But it does mean I get to work with art, and write about art, and plan exhibitions, and help produce exhibitions, and other art-adjacent things. So I am a lucky man.

That’s way more than you need to know about me! So what will this blog be about? Well, anything, I guess, but likely topics are: my podcast, literature, art, comics, autism, typography, art history, traveling, my dog (who I haven’t mentioned yet), creativity, intellectual property, web design, history, parenting, and, I don’t know…maybe a recipe or two?

I hope you’ll find something to think about here, either in the archives of posts I’ve migrated from Blogger or in the posts yet to come. You can also subscribe and get new essays in a convenient e-mail format! I think. I am still figuring that out as well.