Boston is a great place for cemeteries. If you visit our fair city as a tourist and walk the Freedom Trail, which is the red-brick line that connects downtown Boston’s and Charlestown’s most famous historic sites, then amongst Revolutionary venues like Bunker Hill and the Old North Church you will also find three cemeteries: Granary Burying Ground, King’s Chapel Burying Ground, and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground. Around these parts, graveyards are called “burying grounds” when they date back to colonial times, which is both charming and kind of spooky, and that makes them even better. Even out in the ‘burbs where I live you will find burying grounds: there’s one in West Roxbury, the Westerly Burying Ground, which dates to 1640. It’s almost invisible from facing Centre street as it’s behind nondescript iron fences and sandwiched between a brand-new condominium building on the left a Walgreen’s parking lot on the right. Except the Walgreens went out of business last year. But we might get a Trader Joe’s in its place!

Aside from burying grounds, there are many other, relatively-newer cemeteries in and around Boston, of which two of the best are sprawling Victorian estates: Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain and Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. Both are full of monuments shaped as weeping angels and half-covered urns and they are still open for new residents if you’re interested, and also have tens of thousands of dollars that you’re willing to skim off your children’s inheritances.

My point is: if you like strolling around beautiful old cemeteries looking at unique and fascinating markers, then Boston has you covered. Listed below are some of my favorite graves, monuments, and markers that you can look for the next time you’re in the area and feeling morbid.

Franklin Monument, Granary Burying Ground

CC Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

https://www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/489221660

Looking into Granary Burying Ground from Tremont Street, the eye is drawn to the enormous Franklin Obelisk, which is not a marker for Benjamin Franklin, who is buried in Philadelphia 300 miles away, but a monument to his parents, Josiah and Aviah. It’s not even their original memorial! This obelisk was erected in 1827 to replace their earlier, worn-out headstones1.

Obelisks were a huge fad in the Victorian era, following the Napoleonic invasion of Egypt in 1798 and the ensuing European excavations of ancient sites. In their ancient, Middle Kingdom usage, obelisks were associated with Ra and placed in front of the sun-god’s temples. 19th Century Europeans adopted the form as a general-purpose monument, and built them bigger and fancier; the most famous example of which (for Americans) being the Washington Monument. Anyway, to return to the Franklin Monument: I cannot over-stress that this is not Benjamin Franklin’s grave. It’s not that the marker is being actively deceiving, but most people will only clock the word “Franklin;” and once when I was walking by I overheard a tour guide tell her audience that this was the final resting place of the famous kite-flyer. So I guess the moral of this is that Ben Franklin is confusing. As the Firesign Theatre put it, the only president of the United States who was never president of the United States.

People will also tell you that Mary Goose—who, unlike Ben, is indisputably interred in Granary Burying Ground—was the original Mother Goose of nursery fame. This is a flat-out lie, and it distracts from the fact that there’s a gravestone for a woman named Mary Goose and that’s delightful enough.

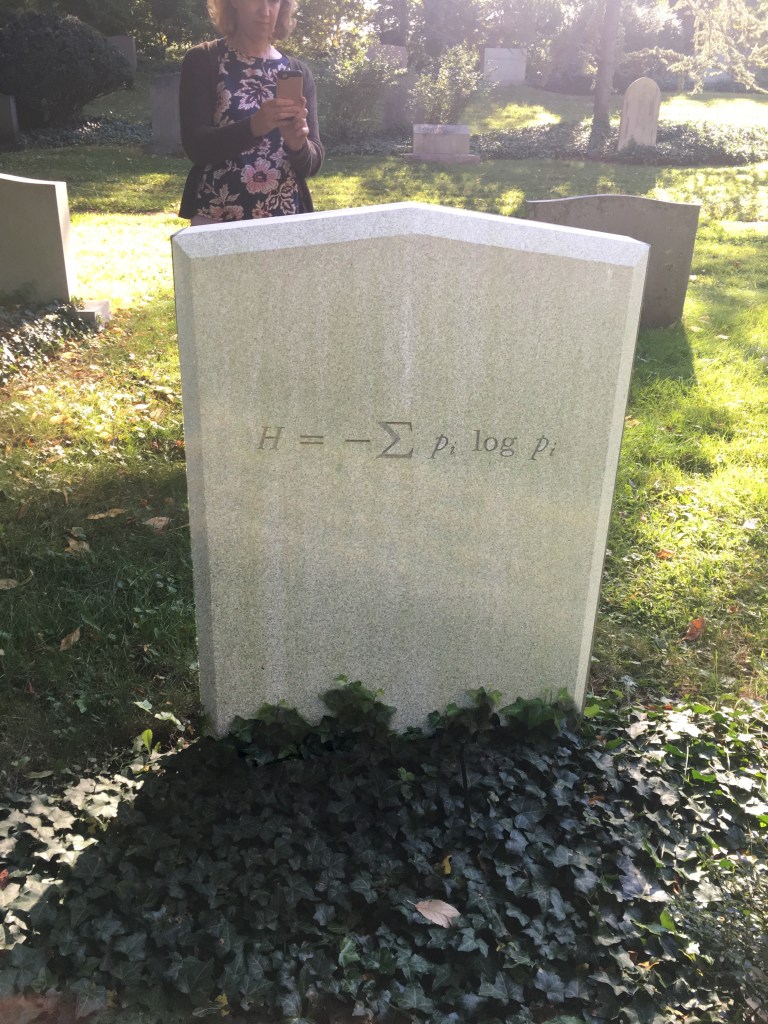

Claude Shannon’s grave, Mt. Auburn Cemetery

On one of our visits to Mt. Auburn Cemetery, my wife Marina spied a marker which appeared to only be a mathematical formula: H = -Σ pi log pi. Intrigued, we circled around the headstone and discovered that its other side was the front, and that this was the gravestone of Claude Shannon (1916–2001), also known as “the father of information theory.”

Shannon was a polyglot: a mathematician, electrical engineer, and computer scientist, who was there when computer science first became a discipline. In his master’s thesis he theorized that Boolean logic could be applied to electrical circuits, which became the basis of digital computing. As if inventing computers wasn’t enough, in a later paper he laid the foundation for information theory by describing a theoretical system for conveying data, which is why we have an Internet.

The formula on his marker is his entropy equation, which describes the level of uncertainty in a communication system—that is, what’s the noise-to-signal ratio a network. In Shannon’s biography A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age, authors Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman noted that Shannon’s children wanted the equation on the front of the grave, but his wife opted for the reverse. However, my wife and I spotted the back before the front, owing to the position of the grave relative to the main path. And honestly? This is the preferable way of viewing the gravestone.

Jules and Jane Marcou’s graves, Mt. Auburn Cemetery

Mt. Auburn has some of the most whimsical graves ever, and amongst the most whimsical are those belonging to natural scientists. Jules Marcou (1824–1898) has a stone which is often mistaken as having the shape of a nautilus shell. But it’s actually modeled after the nautilus’s extinct prehistoric cousin, the ammonite, a class that is closer genetically to octopi and squid. Ammonites are particularly interesting to geologists and paleontologists because there were many thousand species of the creatures over the course of 344 million years, from the Devonian period to the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. The practical upshot of this is that fossils of ammonites (which are bountiful) are helpful markers for determining just how old the geologic layer you’re looking at is.

Which is why an ammonite rather than a nautilus is an appropriate marker for Marcou, who wasn’t a marine biologist but a geologist. Marcou divided his working life between Switzerland and the United States, eventually co-founding (along with Louis Agaaaiz) the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard.

Alongside Jules lies his wife Jane (1818–1903). From those dates we can see that Jane was Jules’s elder by six years, which may not seem like much, but which is remarkable for an era when men generally married much younger women. They married in 1850 when Jane would be 32, so good on you guys for bucking convention. I don’t know if the oak leaves on her stone have any specific significance—oaks are generally associated with strength and longevity. But I do know that the marker pairs beautifully with her husband’s in size, color, and detail.

Dog monuments, Mt. Auburn Cemetery

Throughout Mt. Auburn there are many stone carvings in the shape of dogs. This doesn’t mean that dogs are buried under the markers. Mt. Auburn officially doesn’t allow pets to be interred (although there are rumors that some have been snuck in); these dogs are symbols of watchfulness and fidelity, standing guard over the human remains. In many folk traditions, Dogs are seen as psychopomps—spiritual guides to the afterlife, who make sure souls make their way safely to the next world. A modern reference to this tradition is in the Pixar film Coco, where the stray xolo dog, Dante, turns out to be an alebrije, a Mexican spirit guide.

The dog shown here has the inscription “1843-M.P.S.-1849” and is the marker for Mary Prentiss Saunders, who sadly died when she was six. I have no way of knowing, but I like to imagine this is a likeness of a loyal pet of hers.

Gracie Sherwood Allen, Forest Hills Cemetery

Many people visit Forest Hills specifically to see “the Girl in the Glass.” The memorial is something of a superstar amongst the graveyard set. However, my family and I stumbled across it by chance and with no prior knowledge while on a summer’s outing in the cemetery. This is, of course, the best way to experience almost anything, but if you’re reading this post then that’s not on the menu. Sorry.

The monument for Gracie Sherwood Allen (1876-1880) is a life-sized marble sculpture of the child, encased in an enclosure of glass something like a tiny gazebo. In her hand, Gracie holds a bouquet of wilting flowers—a bit on the nose, even for Victorians. If you aren’t expecting it, or even if you are, it can be unnerving, but in a sweet and sad sort of way. Gracie died before her fifth birthday from whooping cough. Sadly, before modern vaccines, childhood diseases were devastating: measles, rotavirus, diphtheria, polio, and pertussis, to name only a few of the worst. When you see life expectancies from years past, it’s the deaths before the age of ten that mostly drag the averages down. If you made it to age six, you had as much a chance of reaching old age as you do today. The moral of this is don’t make RFK jr. secretary of health and human services.

Many descriptions of this grave make little or no mention of the monument’s creator. In this piece by WBZ News Boston he’s simply called “a local sculptor2.” The artist in question was Sydney H. Morse (1832–1903) and he was a fascinating character: a Unitarian preacher, an anarchist, editor of the Boston magazine The Radical, and a self-taught sculptor and painter who never quite made it in the art world. He specialized in portraiture, mostly of historic or famous figures. He had a correspondence with Walt Whitman over some likenesses Morse made of the poet. While we don’t know if the sculptures mentioned in these letters met with approval, we do know that Whitman called an earlier bust of himself by Morse “wretchedly bad.”

Here’s a TikTok by user @ghoulplease_ that provides many views of the statue, as well as giving a nod to Forest Hill’s other child under glass (they have two!):

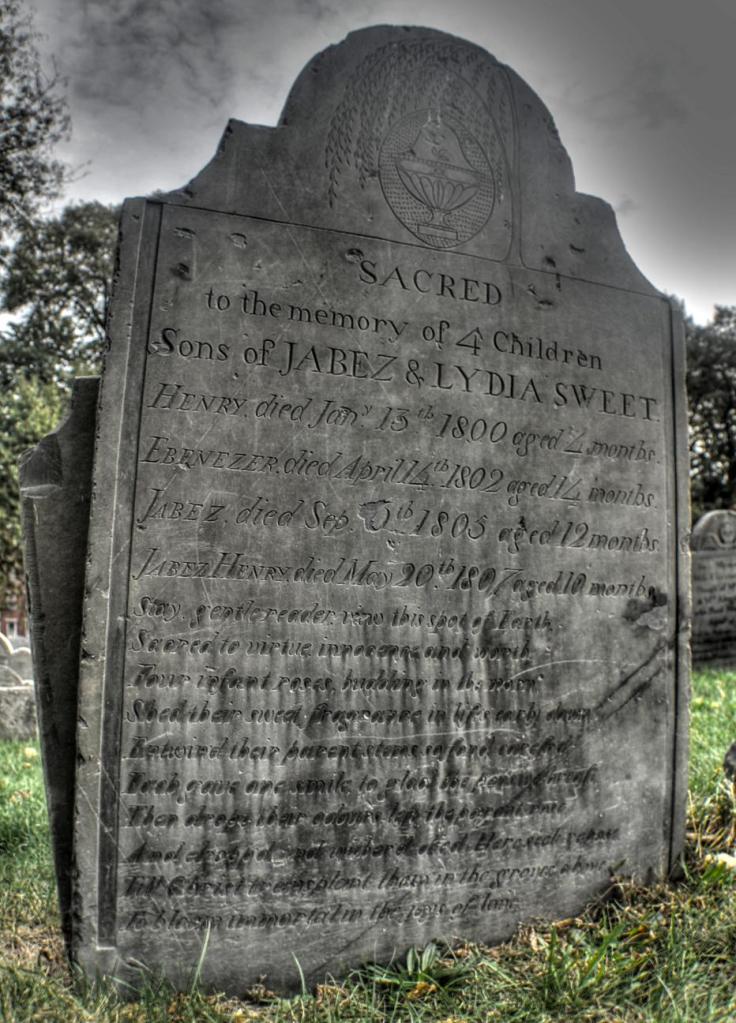

Sons of Jabez and Lydia Sweet, Copp’s Hill Burying Ground

What’s sadder than a gravestone for a child? How about one for four children? Henry, Ebenezer, Jabez, and Jabez Henry Sweet, aged four, fourteen, twelve, and ten months respectively, share a single grave, erected some time after the last death in 1807. This is a later grave for Copp’s Hill, which was established in 1649 and which is mostly comprised of colonial stones, including many figures from the revolutionary period.

CC Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jeremyfarr/2222911091

The Sweet children’s marker tells a sad but incomplete story. The names Jabez and Jabez Henry indicate that the parents were hoping for a (male) heir but meeting tragedy after tragedy. However, we don’t know if their were other children born before, during, or after these attempts. The death years are 1800, 1802, 1805, and 1807, which sounds absolutely exhausting for poor Lydia Sweet, but given the expectation of the times I wonder if another child, perhaps a daughter, was born between ’02 and ’053.

The stone has a beautiful, heart-rending poem, with a sophisticated extended metaphor of roses written by someone who must have been a gardener:

Stay, gentle reader, view this spot of earth,

Sacred to virtue, innocence and worth,

Four infant roses, budding in the morn,

Shed their sweet fragrance in life’s early dawn,

Entwin’d their parent stems, so fond careſ’d4

Each gave one smile, to glad the pensive breaſt,

And dropp’d and wither’d, died! Here seek repose,

Till Christ transplant them in the groves above,

To bloom immortal in the joys of love.

Quentin Compson III Memorial, Anderson Memorial Bridge

To end this post on a happier (?) note, I wanted to finish this list with a marker commemorating the death of someone who never lived: Quentin Compson III, a character who first appeared as a main character in William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury (1929) and later in Absalom, Absalom! (1936). In Faulkner’s works, Quentin is a neurotic young man, the offspring of a once-prosperous Southern family whose fortunes have fallen to the point of selling off their plantation parcel by parcel. In Faulkner’s books Quentin attends Harvard University, where he struggles with guilt over his family’s history and with the disappearance of his sister Caddy, who ran off in the night. To his Northern classmates, Quentin is an exotic curiosity, and his roommate grills him on his ambivalence to the South.

The Sound and the Fury is a notoriously opaque book, full of jumbled chronology, competing points of view, and streams of consciousness. So while Faulkner doesn’t directly depict it, the reader can eventually tease out that Quentin commits suicide by filling his jacket’s pockets with flatirons and jumping off a bridge—unnamed by Faulkner, but generally believed to be the Anderson Memorial Bridge, which on the Cambridge side leads directly to Harvard Square.

In 1965 a mysterious brass plaque, only large enough to cover a single brick, appeared on the interior wall of Anderson Bridge by the pedestrian path. It read:

Quentin Compson III

June 2, 1910

Drowned in the Fading of Honeysuckle

Faulkner used the word “honeysuckle” 29 times in TSatF—all but one of them in Quentin’s point-of-view section, where he wanders about Harvard planning his eventual demise. Who placed the plaque initially was a mystery, as was whomever replaced it in 1975 following its accidental removal during renovations. That replacement plaque altered the text to “Drowned in the Odor of Honeysuckle,” which fans of the monument mostly found inferior. In 2017, following yet another renovation, a new plaque was placed on the exterior of the bridge on the downstream side, this one restoring the original wording.

A 2019 Harvard Gazette article attributes the original plaque’s placement to Stanley Stefanic, Jean Stefanic, and Tom Sugimoto, in a ceremony to commemorate the 55th anniversary of Quentin’s (literary, not literal) death.

- The senior Franklins’ graves didn’t even last a century after their deaths. I hope they didn’t pay a lot. ↩︎

- This article also claims that there is an “eagle sculpture atop a headstone that was the basis for the golden sculpture that greets visitors by the main entrance [to Boston College].” Well Mr. WBZ, that is a straight-up falsehood. I work in the museum that houses the original eagle, and it’s a Meiji period bronze, most likely executed by Chōkichi Suzuki (1848–1919). ↩︎

- There were more Jabez Sweets in New England in 1790-1820 than you would believe; however, if the Lydia Sweet in this family tree is the right one, it appears she did have at least two daughters that survived into adulthood. ↩︎

- There are two long letters S in this poem. The general rule for this character, when it was in fashion, was to use it when an S appeared in the middle of the word; starting and ending letters were the round S’es we have today. However, the poet (or engraver) missed one on “pensive.” Also they use the word Till when they wanted ‘Til. Sorry, this is the stuff I think about. ↩︎

Links

The official Freedom Trail site has more information on Granary and Copp’s Hill Burying Grounds:

https://www.thefreedomtrail.org/trail-sites/granary-burying-ground

https://www.thefreedomtrail.org/trail-sites/copps-hill-burying-ground

A nice blog post about Claude Shannon and his grave:

https://parkerhiggins.net/2017/09/a-mind-at-play-and-claude-shannons-grave/

Here’s an article discussing even more of the adorable dogs of Mt. Auburn:

http://cambridgecanine.com/2011/10/the-dogs-of-mount-auburn-cemetery/

Here’s an extensive article on Sindey H. Morse’s anarchistic politics:

https://www.libertarian-labyrinth.org/sidney-h-morse/horace-traubel-remembers-sidney-h-morse-1903/

Here’s much, much more information on the Quentin Compson plaque:

https://historycambridge.org/articles/the-mystery-plaque/

Here’s my Sophomore Lit podcast covering Absalom, Absalom! I realize that I still haven’t done an episode on The Sound and the Fury:

https://www.theincomparable.com/sophomorelit/40/