Header image: S.O. Grimes general store, Westminster, Md., c. 1900. Image via Library of Congress.

Another day, another shot fired in the culture wars: this time, the internet is losing its collective mind over the new logo for Cracker Barrel. If you are unaware of the controversy, congratulations—you might consider skipping reading the rest of this essay to remain in blissful ignorance.

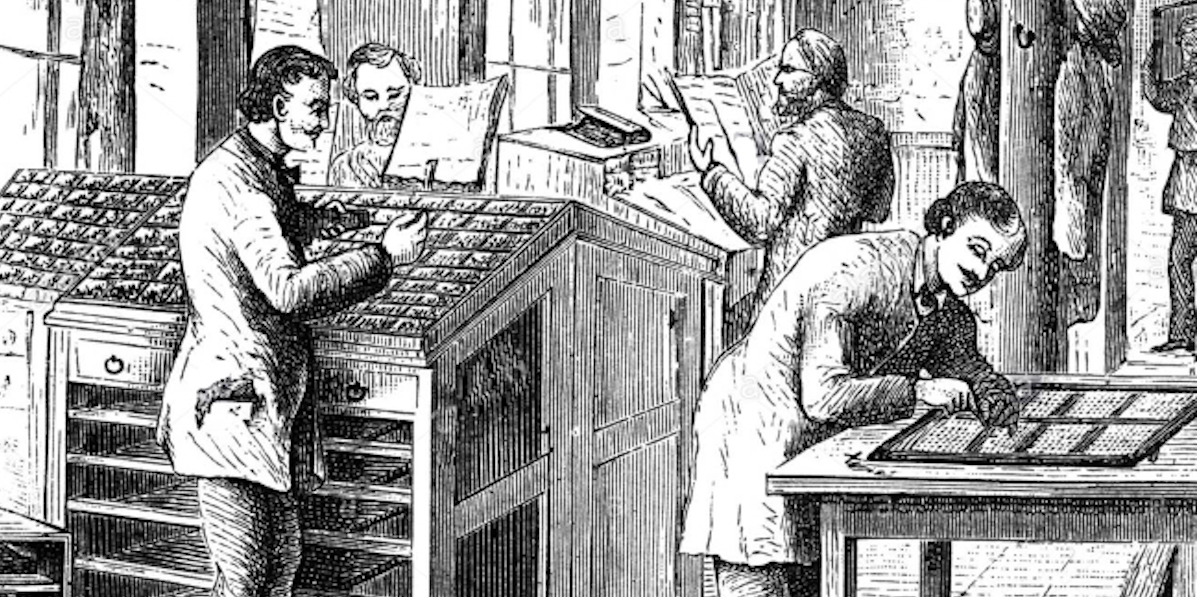

To summarize: Cracker Barrel, that paragon of blandly inoffensive roadside dining, has decided that its long-standing theming to evoke early 20th century general stores might be limiting its appeal to Gen Z, and so has embarked on a brand makeover that downplays the hokey country charm. Part of this rebrand is a simplified logo that ditches an illustration depicting a gentleman in overalls perched on a wicker seat ladder back chair and leaning against the titular barrel. (This man, “Uncle Herschel,” was a real person.)

To say that the change has not been taken well by the chain-restaurant-going public would be an understatement. Some of those seeing red also see a political conspiracy—from “influencers” who say that the logo is stripping culture and heritage away from rural white Americans, to Fox News hosts claiming that corporate moves such as this logo change are why President Trump needs to send troops to Chicago. Underlying these criticisms is the assumption that the rebrand is part of an insidious “woke” movement perpetrated by American businesses.

The truth is, no corporation wants to touch anything political with a twelve-foot pole, especially these days. Look at what happened to the department store Target, which caught flack from the right for daring to stock pride merchandise, only to get hit even harder from the left for caving to anti-DEI pressure. Walmart and Amazon have also been subject to boycotting headaches over DEI policies and allegations of abetting the Trump administration. No, politics have nothing to do with the decision to change the Cracker Barrel logo—although it remains to be seen if political outrage from consumers can be sustained.1

The rebrand reminds me of a similar kerfuffle last year involving the British confection Lyle’s Golden Syrup. Americans may be confused that such a product exists in the first place; but they would be even more baffled by the logo for the sugar refinery Abram Lyle & Sons, which consists of bees swarming about the corpse of a lion. The company’s motto, “Out of the strong came forth sweetness” points to the source of this imagery, the biblical tale of Samson’s riddle2. All of which is to say that this is the most badass logo ever, as well as being an amazingly long-lived one—it dates to 1883. In 2024, Lyle & Sons decided that this work of art was too morbid, and replaced it with a more anodyne illustration of a syrupy lion. This change was also greeted with political accusations.

But just because I doubt that these choices were motivated by politics doesn’t mean the detractors don’t have a point: something basic is being lost here. In both cases the companies have discarded character and context in an effort to streamline their identity. I have written previously about the often misguided penchant art directors have towards simplifying their brands. I suspect that the lion’s share (ha) of this tendency is simply following trends, and the current fashion in corporate design is simple, flat typography and short (often single-word) brand names. To the extent that someone actually gave this a thought, the rationale is to remove any attributes that might complicate a consumer’s attitude towards the brand. It also reflects the desire of new executives to mark their territory by peeing on it—see HBO’s constant rebranding, or Elon Musk destroying the only part of Twitter that had any value, its name recognition.

If you want to be charitable, and I try to be when I can, the move towards brand simplification also reflects a longstanding adage in design—be it visual art, design, writing, or engineering: “less is more.” This saying, often misattributed to Mies van der Rohe, emphasizes clarity and utility. The goal is to focus on what is essential. Practitioners of this belief make outsized claims about the effects of this approach. In his seminal work Understanding Comics (1993), cartoonist Scott McCloud claims that idiographic drawings amplify meaning. He also claims that in simplified, “cartoony” design, viewers can insert themselves into the depiction3. I love McCloud to pieces but this all seems a bit farfetched to me.

There’s a lot to be said for purposeful simplicity. Growing up in the 70s and 80s I was surrounded by, and loved, logos by Saul Bass, Milton Glaser, and Paul Rand, all of whom were known for absolutely iconic, geometric, minimalist designs. But these artists, working before digital tools, had to visualize their designs as tight, abstract forms. They did not select something they liked from the font menu, slap it on a generic color shape, shut down Adobe Illustrator and call it a day. Even at their simplest, the great Modernist graphic designers had a sense of context and of play. They weren’t afraid of their work conveying an attitude.

And it’s attitude that’s missing from the Cracker Barrel rebrand. The original logo wasn’t great, in much the same way that the actual restaurants aren’t great. But it did have a point of view, and that’s what the new design is lacking. As a rule of thumb, good design is supposed to not draw more attention than the message it conveys. But when design fades away into no design, the message also disappears. When you look at the new Cracker Barrel logo, ask yourself: would you even know what good or service it represents if you didn’t already know the brand name? Here, look at what happens when you replace the words:

Is it a clothing line? Is it a cake mix?

- It also remains to see if Cracker Barrel is going to remain committed to this rebrand, given the fact that their stock is being absolutely destroyed. ↩︎

- If you’re not familiar with the Book of Judges: Samson, on the way to visit his future bride Timnah, is set upon by a lion. The hero kills the beast with his bare hands. Sometime later he returned to the scene of the attack and found that a colony of bees had made a hive in the lion’s body. Samson eats some of the honey. Returning to marry Timnah, he tells the bridal party (made up of Philistines, who are his sworn enemies) that they must answer a riddle or forfeit their clothes: “Out of the eater, something to eat; out of the strong, something sweet.” Ultimately this story does not end well for Samson, Timnah, or the Philistines. ↩︎

- Amusingly, in his essay “Modern Cartoonist,” comics artist Dan Clowes takes exception to McCloud’s theory: “Comics tend to lean toward the iconic (‘The Adventures of a featureless blob'”‘) because it encourages reader identification. Let’s get away from this arena of vagueness (a cheap gimmick designed to flatter the shallow reader)” Eightball 18, 1997. ↩︎