Back in the days when Halloween was primarily a night for kids to knock on doors to get stray change and popcorn balls; back before the holiday morphed into an excuse for young adults to dress as sexy versions of 90’s cartoons and get their slutty drink on; that is, back in the 70s, store-bought costumes were crap. They consisted of thin vacuum-formed plastic masks and silkscreened bodysuits which were made of a mystery fabric that was not quite muslin, not quite plastic, but 100% flammable. Eventually even this material was deemed too costly to produce and the suits were made entirely from vinyl, lending them all the drape of a deflated beach ball. These were the ubiquitous licensed character costumes made by Ben Cooper, inc., which, defying all reason, are highly collectable today. Nostalgia is a hell of a drug.

Of course, there were kids and parents who wished to avoid paying a whopping three bucks for commercially-produced outfits that were only marginally recognizable (owing to the fact that they had the characters’ names emblazoned on their chests). For the non-conformists, costumes of hoboes, pirates, ghosts, and mummies were good options because you could make them out of last year’s ratty clothes and sheets and felt and other bits of stuff lying around (toilet paper was often involved). But for the true weirdos, those who aspired to be something scary or gross for Halloween, there was only one game in town, and that was the Imagineering line of makeup and prosthetics. They were cheep, funky, grungy, and surprisingly effective, especially when it came to making gaping wounds and the like, and I loved them so much.

Instead of selling full costumes of specific characters, the Imagineering line consisted of theatrical building blocks you could mix and match. There were evil teeth and fake fingers. There was fake blood and tooth blackout. And there were small pallets of ingenious stage makeup, such as Scar Stuf™, a mixture of beeswax and cotton fibers that seemed like it couldn’t possibly work but which did in fact produce startlingly realistic scars, wounds, and other abrasions.

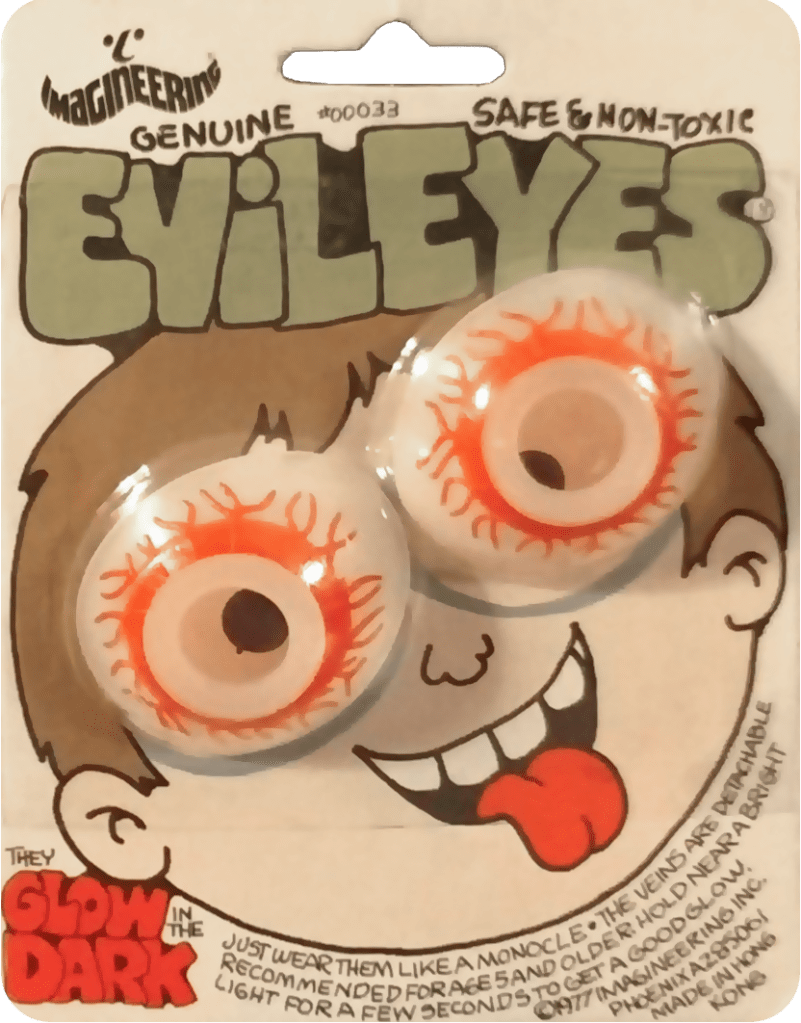

For much of my childhood I was limited to the pointy teeth and fake blood. I was not particularly flush as a kid, and while most items in the Imagineering line ran 50-75 cents, that was still a lot for me. Until one October—maybe ’78 or ’79—when I finally had some income of my own from delivering The Peoria Journal Star (afternoon edition). That year I finally splurged on a pair of Evil Eyes, the prosthetic eyes that GLOWED IN THE DARK. In light they were just a couple of ovals of plastic but in complete darkness, they were Fire from the Very Depths of Hhell. To maximize the glow effect, I would hold the plastic eyes under my reading lamp—a gooseneck 75 watt lamp clipped to the headboard of my top-level bunk bed—for about five minutes. Then I would run to the darkest place in the house (mostly under a blanket in my closet) and stare in horror at the glowing orbs until they faded into blackness. Of course, like all glow-in-the-dark toys, the magic was over far too soon, and the best effect could only be achieved by holding the eyes a long time as close as I could to the incandescent bulb, which was blisteringly hot. To save my fingertips, I took to placing the eyes on my bed and bending the lamp down as close as I could. One day I decided I would get the best glow ever by bringing the lamp down so that the hood touched my quilt and the bulb pressed against the eyes, shutting the precious lumens in entirely. Pleased with this set-up, I went off to get a snack before I would take the eyes into the dark.

Two hours later, my mother came into the living room where I was sitting reading and asked if I smelled something funny. My father also was alarmed. We walked down the hall and it became apparent that thin black smoke was coming out of my bedroom door. When we entered there was a cloudy, oily plume coming from under my lamp, which was still directly on my quilt. My father grabbed a sock to push away the lamp, which had deformed from the heat. We were greeted with a massive billow of inky miasma; and underneath, a soupy, sticky mess of plastic making tendrils from the bulb to the quilt, which now had a smoldering hole in one block. My shocked parents asked me what on Earth I had been doing and I was at a loss to explain myself. Secretly, all I could think of was if there were a way to block out the windows because holy hell, those goopy, melted eyes would’ve glowed like the sun.