Content warning: this post contains nothing but digressions.

Typography is a mess. Or at least, its argot is a mess. In an earlier post I discussed the various meanings of the word font. An even more schizophrenic typographical term is Gothic, which is most often used to refer to typefaces that imitate Medieval Blackletter hands. Blackletter itself isn’t a specific typeface—the term predates typefaces—it’s a family of associated hands, and a hand is a standardized manner of forming letters by writing. As opposed to inscription, which is the primary way we know the original Latin alphabet (which is also variously called a Roman or Antique alphabet, depending on where you’re from).

Blackletter was used in Western European scriptoriums starting in the 12th century, and was designed as a decorative style that could be uniformly employed by trained scribes; it is characterized by extremes of thick and thin lines and letterforms that show the individual strokes by which they are made using broad pen nibs. This broken, fractured quality of Blackletter is reflected in the name of a German subset of styles: Fraktur, which was used in Germany and the Baltic states from the 16th Century on up to the 1930s. As they rose to power, National Socialists used Fraktur in printing as a marker of German identity, which is why Blackletter has a contemporary association with Nazism—even though Hitler himself hated the form and outlawed its use in 1941.

Graphic by Manuel Strehl CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12778207

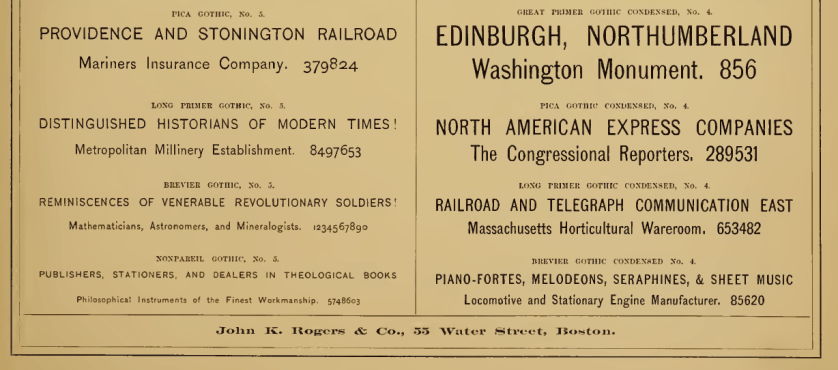

But to return to the word Gothic: in the United States, this word has, since the 19th Century, been used typographically to describe geometric, unilinear, sans-serif typefaces. It’s unclear why this usage was chosen, although it is likely related to the European term for this style, Grotesque. While today the word grotesque is synonymous with deformed, repulsive, or bizarre, the word literally means “coming from the cave,” and referred to designs found in underground Roman ruins from the time of Nero. When discovered in the 1500s, these ruins were called le Grotto, in spite of not being a cave at all, but the basement to an unfinished palace complex. But in the Rococo period, artists and architects went crazy for these roman wall decorations and adapted them into increasingly complex and ostentatious patterns of their own, which they called Grotesques. In the 17th century, these extravagant and fantastical motifs were criticized as distorted caricature, leading to the modern, disparaging use of the word, which is an unusual transformation in art history, where for the most part terms coined as ridicule eventually lost their negativity: Impressionism, Pointillism, Fauvism, Cubism—or even, Gothic.

Victoria and Albert Museum.

But to return to typography—which is the ostensible subject of this essay—the typographic term Grotesque (or its German form still seen in many typeface name, Grotesk) was likely used to mean “unorthodox,” or “brutal.” In this manner it is like the original architectural term Gothic, coined in 1550 by Giorgio Vasari, meaning “of the Goths.” This, as mentioned above, was not a compliment—Vasari was comparing the new style’s displacement of Italianate forms to the conquest of Rome by barbarians. (Which is another pejorative word meaning “bearded,” because beards were considered uncultured.) It may be that this usage of Grotesque informed the American term Gothic, similarly used to refer to typefaces that were stark, Spartan, dispensing with cultural niceties like serifs, which were, after all, vestiges of writing text by hand. Or maybe not! Who knows! All that is certain is the term was first used in the 1830’s by the Boston Type Foundry to describe its line of geometric, mono-line, sans serif typefaces.

Oddly enough, at about the same time, American typographers began to use the term Egyptian to refer to mono-line slab-serif typefaces. This may have been because they recalled hieroglyphs—Ancient Egypt was something of a fad, owing to the era of modern archeological excavations as carried out by Napoleonic surveyors in the early 1800s.

Or maybe not. As I said, typography is a mess.