Note: this is another companion essay to an episode of podcast, Sophomore Lit. Maybe listen to it before reading this?

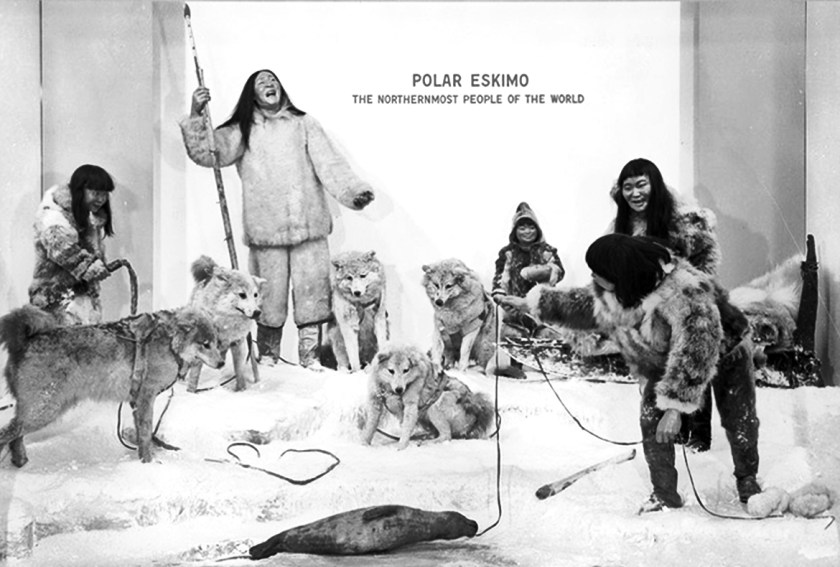

Shortly after recording the most recent Sophomore Lit episode about Robert Westall’s young adult novel The Watch House (1977), guest host Ross Cleaver pointed me towards an online discussion about a magic lantern series called Our Life Boat Men. While most of the eight-slide series features scenes of rescues involving life boats, there is one slide that depicts a rescue using a rope line and pulley, the technique that Westall describes in his book.

Image from Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums.

Magic lanterns were a form of image projector popular in the 19th and early 20th century. The ability of curved glass to bend light was known from antiquity, with the earliest written reference appearing in Aristophanes’ The Clouds. Reading-stones (rounded glass magnifiers) and even spectacles were used in medieval times. But modern lenses as we know them started in the 17th and 18th century with the development of the telescope and the microscope. By the 19th century optics had become precise enough to sharply focus projected light. This development, along with increasingly bright light sources, such as gas and limelight, led to the commercial production and popularity of magic lanterns.

These projectors used glass slides that came in a variety of sizes upon which were the images to be projected. The first slides were hand-painted, but later, photographic techniques allowed for mass replication. At first, publishing companies mechanically transferred black line images to the slides, most commonly using decals; colors (if any) still had to be added by hand. But at the end of the 19th century chromolithography and semi-transparent inks made possible printing uniform editions of magic lantern slides, albeit with often imperfect registration of colors, as is evident from “The Pulley.”

The series Our Life-Boat Men was sold as a part of London-based W. Butcher & Son’s Junior Lecturer’s Series. While the slides themselves are undated, a 1901 advertisement lists Our Life-Boat Men as one of six “new” lithographic sets produced to be used with their Primus line of lanterns. Butcher & Sons aimed at a market of well-to-do home users, and their chromolithographic slides were relatively inexpensive when compared to ones designed for theatrical use—and yes, in the 19th century people did pay admission for the privilege of viewing still projections in darkened rooms.

In Westall’s book, the book’s protagonist Anne is told of the techniques employed by the Victorian life-savers who used to work at the titular watch house. The port of the novel’s fictional town of Garmouth (based upon Westall’s hometown of Tynemouth) is bounded on its sides by shallows covered with mounds of rock, and in bad weather ships could beach themselves only a few hundred feet from shore. The watch house volunteers would shoot ropes to the ships using rockets and survivors could be drawn ashore using pulleys. As I mention on the podcast, when I read these passages—describing rescues carried out in the 1850’s—I was incredulous. It didn’t seem possible, especially with 19th-century rockets, to fire with such accuracy while dragging 20 pounds of rope (or more). But apparently this was a widely-used technique. The Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum of displays examples of the apparatuses that were employed.

Image by Geni, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

In the slide “The Pulley” the intrepid hero is riding in a lifebuoy that is hitched to a hoist trolley—if something goes wrong, at least he has a flotation device. In his arms he appears to be holding a child wrapped in a tattered red blanket. The rescuer is lightly dressed for such cold weather, although he wears a sou’wester oilskin hat, which is standard rough weather maritime gear. There are narrative details that make me wonder. Why is the man barefoot? Is that standard practice, or did he loose his boots in the operation? He appears to have a strand of kelp trailing from one foot. Does this mean he’s grazing the water? Is he in danger of submerging? Come to think of it, how can the rope be staying that taut? Wouldn’t it dip with the weight of the passengers?

But mostly: Why can’t I stop obsessing over random bits of forgotten culture?